A Quick Glimpse of Obon

Obon (お盆) is Japan’s midsummer home‑coming: a three‑day period when families gather in the belief that their ancestors’ spirits return. Lanterns are lit to guide their souls, graves are cleaned, and community squares fill with rhythmic Bon Odori dances. Although Obon is not an official nationwide holiday, many companies close, trains overflow with travelers heading back to their hometowns, and city streets take on an almost dream-like calm. For foreign residents, the holiday is a window into Buddhist traditions and a chance to take part in some of Japan’s most welcoming local festivals.

Understanding the Spirit of Obon in Japan

Obon grew from a Buddhist tale in which offerings freed a suffering soul, and this story gradually blended with Japan’s deep reverence for ancestors. By lighting lamps, offering food, and visiting graves, the living ease the journey of the dead and, in turn, feel supported by family lines that reach far beyond one lifespan. This interplay of memory and celebration explains why Obon is at once solemn and joyful.

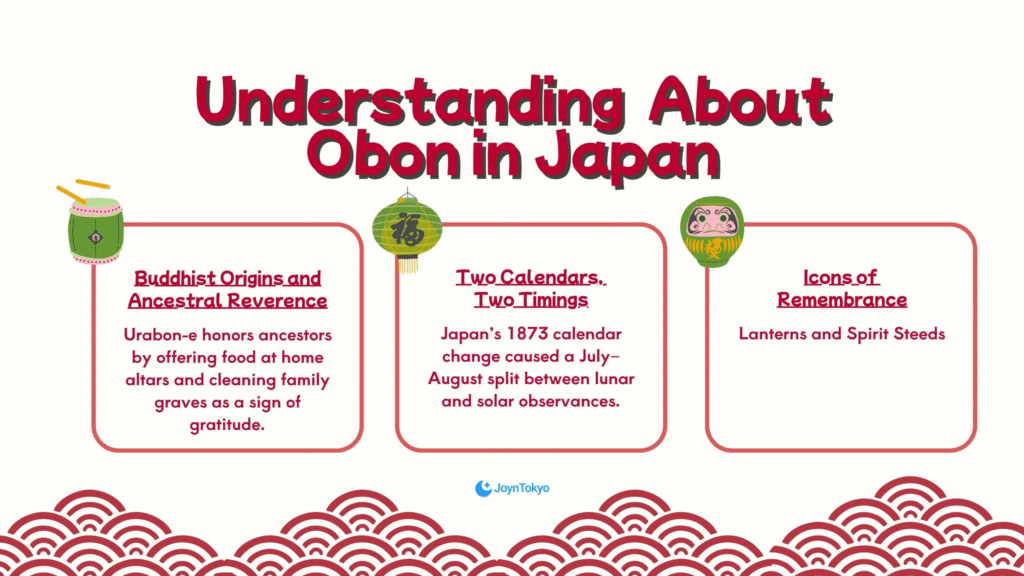

Buddhist Origins and Ancestral Reverence

The term Urabon‑e — a translation of the Sanskrit “hanging upside down” — describes spirits released from torment. Today, households decorate butsudan altars in their homes with flowers, incense, and seasonal fruits, inviting their ancestors to “sit upright” in comfort. Traveling to the family grave (ohaka‑mairi) to scrub, rinse, and decorate the stone is perhaps the most tangible act of gratitude.

Two Calendars, Two Timings

When Japan adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1873, some regions kept the lunar schedule while others switched to the solar one, creating the July/August split. Knowing which system your locality follows will save you from turning up a month too early — or too late — for the neighborhood Bon-odori dance.

Icons of Remembrance: Lanterns and Spirit Steeds

Paper chōchin lanterns line garden entrances so that ancestors can see the way. Families fashion tiny “spirit steeds” from cucumbers and eggplants — representing quick horses for the arrival, patient oxen for the return — symbolizing both eagerness to arrive and reluctance in parting.

Start Your Own Japan Journey With Expert Guidance

Most people never make it to Japan because the start is confusing and tiring. Wrong visa route. Underestimated budget. Months lost to confusion.

Get personalized support for your new life in Japan.

Book Your FREE Consultation✓ 500+ Bookings ✓ English-speaking Relocation Support Experts

Travel Realities During Obon

Although Obon is not a legal public holiday, it functions like one. Banks, factories, and many offices shut for three to five days, and prices for trains and hotels surge. Planning ahead is the difference between a smooth spiritual getaway and spending half the holiday in transit queues.

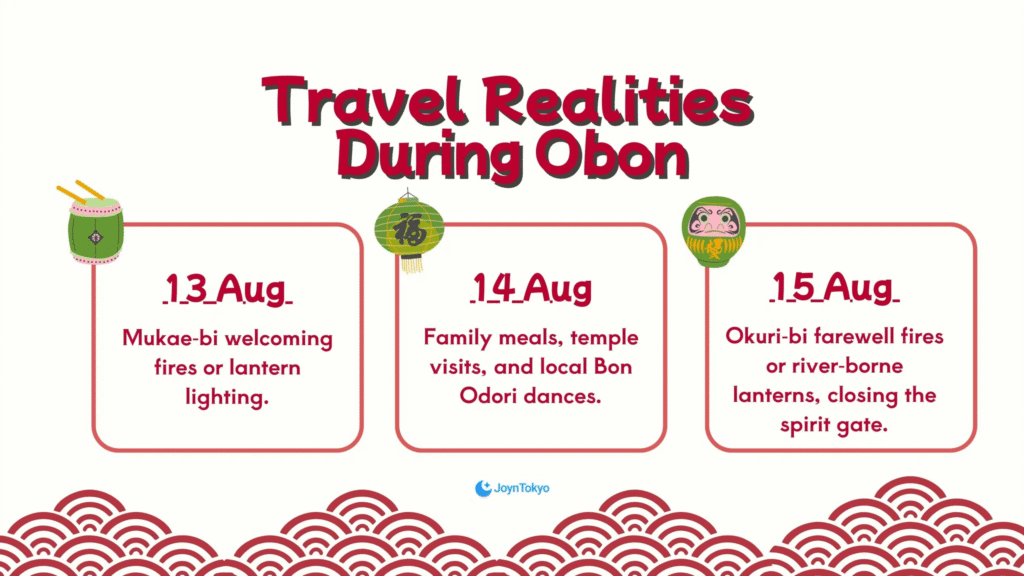

The Typical Three‑Day Flow

- 13 Aug (13 Jul in early‑Bon areas): Mukae‑bi welcoming fires or lantern lighting.

- 14 Aug: Family meals, temple visits, and local Bon Odori dances.

- 15 Aug (sometimes 16 Aug): Okuri‑bi farewell fires or river‑borne lanterns (tōrō nagashi), closing the spirit gate.

Business Hours and Public Services

Municipal offices usually stay open, but small shops and clinics may post handwritten holiday notices. Convenience stores keep their 24‑hour rhythm, yet rural post offices frequently close, so post any parcels early.

Transport Crowds and Seasonal Pricing

Japan Rail opens extra shinkansen carriages for the holidays, but reserved seats sell out a month in advance — the moment ticket windows open. Highway toll discounts are lifted during the peak “U‑turn rush,” and domestic airfares can double. Booking your time off and transport by May is wise, as booking in late July often means standing‑room only.

Celebratory Customs You Can Join

While the spiritual core belongs to the family, most outward rituals warmly welcome newcomers.Even a modest neighborhood Bon Odori can leave lasting memories of taiko drums echoing through the humid night air.

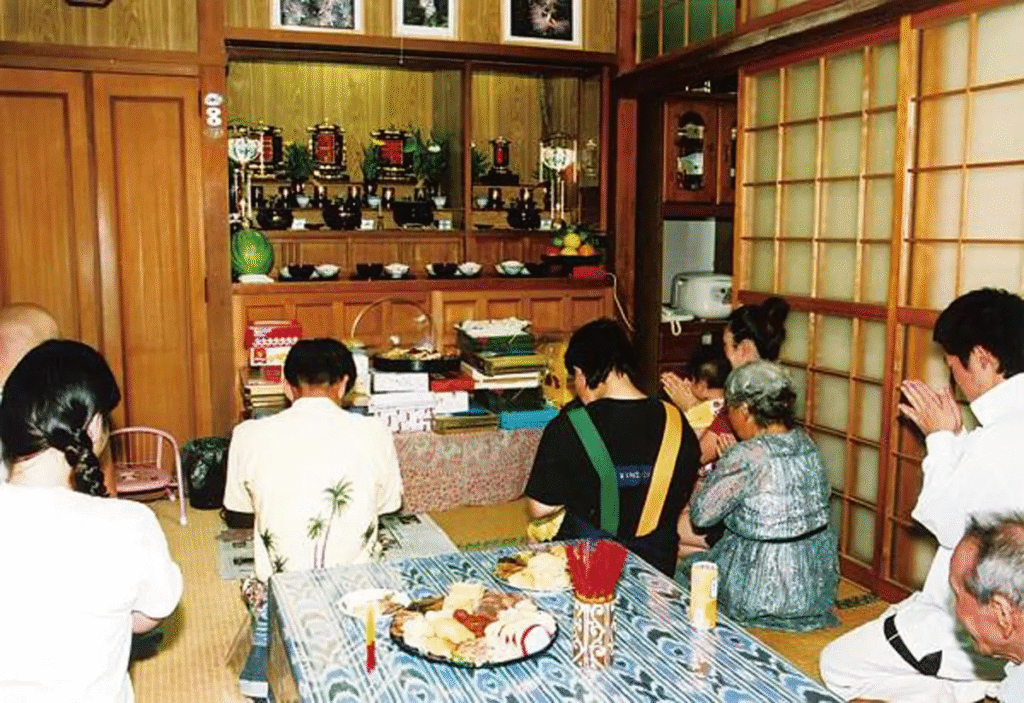

Home Altars and Family Gatherings

Grandparents show children how to fold lotus‑shaped offerings, while younger relatives prepare plates of ohagi sweet rice cakes. Story‑telling about past generations is as essential as any formal prayer, bringing living relatives tighter together.

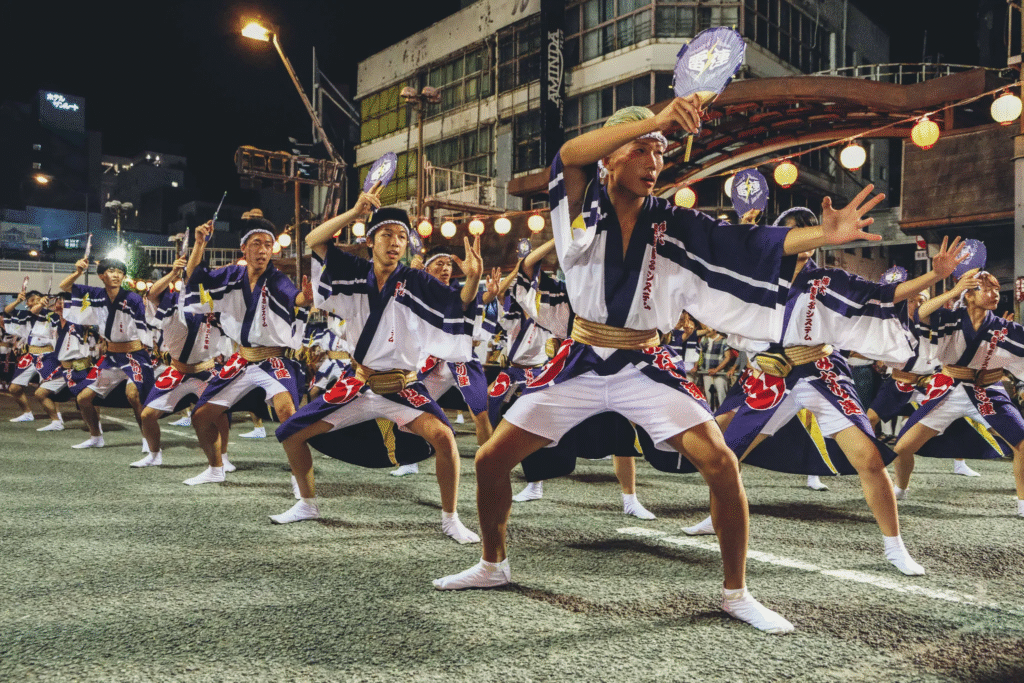

Bon Odori Community Dances

At dusk, volunteers raise a yagura band‑stand wrapped in red‑and‑white stripes. Drummers set a steady beat, singers call the steps, and crowds move in circles that are simple enough to learn after two or three repeats. Lightweight yukata robes add color but are not mandatory.

Tōrō Nagashi: Lanterns on the Water

On the final night, candlelit lanterns drift peacefully down the rivers of Japan. The slow‑moving lights symbolize spirits gliding home, a luminous farewell that blends sorrow, beauty, and gratitude.

Practical Etiquette for Foreign Residents

Joining in during Obon is easy, but be aware that respect is necessary during this holiday.

Joining a Bon Odori

If you rent a yukata (¥3,000–5,000), attendants will help you tie the obi sash. Follow the lead dancers on the yagura stand **— their arm motions often mimic farming, mining, or rowing actions. Keep gestures small and synchronized rather than flamboyant.

Visiting Graves or Temples

Bring a small bouquet and incense sticks. Bow at the gate, rinse hands where a basin is provided, and speak softly. Many families appreciate help carrying water buckets, but always ask first.

Coping with Summer Heat

Kansai afternoons can exceed 35°C heat, with humidity over 80%. Pack a folding fan, hydrate often, and reward yourself with kakigōri shaved ice or chilled sōmen noodles sold at festival stalls.

Festivals Worth the Trip

Japan hosts hundreds of regional events, but three stand out for atmosphere and scale.

Kyoto Daimonji Gozan no Okuribi

On 16 August, five giant bonfires blaze on Kyoto’s surrounding mountains, and the 200‑meter “大” character on Mount Daimonji is visible across the city. The spectacle lasts only half an hour, but the hush that settles over the streets is unforgettable.

Tokushima Awa Odori: Dancing Fool’s Paradise

From 12 to 15 August, 100,000 dancers fill Tokushima’s streets, chanting “Yatto sa!” while shamisen and taiko unite in a hypnotic harmony. Paid grandstand seats start at ¥1,000, whereas the free street areas invite spontaneous participation.

Gujo Odori: Gifu’s Overnight Street Dance

Running 32 nights from mid‑July, Gujo’s climax is the four‑night tetsuya odori (all‑night dance) around 13 to 16 August. Cobblestone lanes echo with wooden clogs until dawn, and the town’s clear streams are the perfect place to cool tired feet.

Why Obon Still Matters — and Why You Should Join In

Obon endures because it marries remembrance with togetherness. Lighting a lantern or dancing under paper lamps turns abstract ancestry into lived community, a feeling that many foreigners find builds a deeper sense of belonging in Japan. Plan ahead, participate humbly, and let this midsummer rite illuminate both the past and present of your Japanese life.