It’s not something anyone relishes, but sadly, it’s a fact of life that most of us, as some time or another, are going to need to go to the hospital. This might be a complex or simple issue in your homeland, depending on where you’re from, but going to the hospital in a foreign country with different norms and procedures might make you nervous. So let me take you through my experience in a week’s stay at a Japanese hospital.

Admission

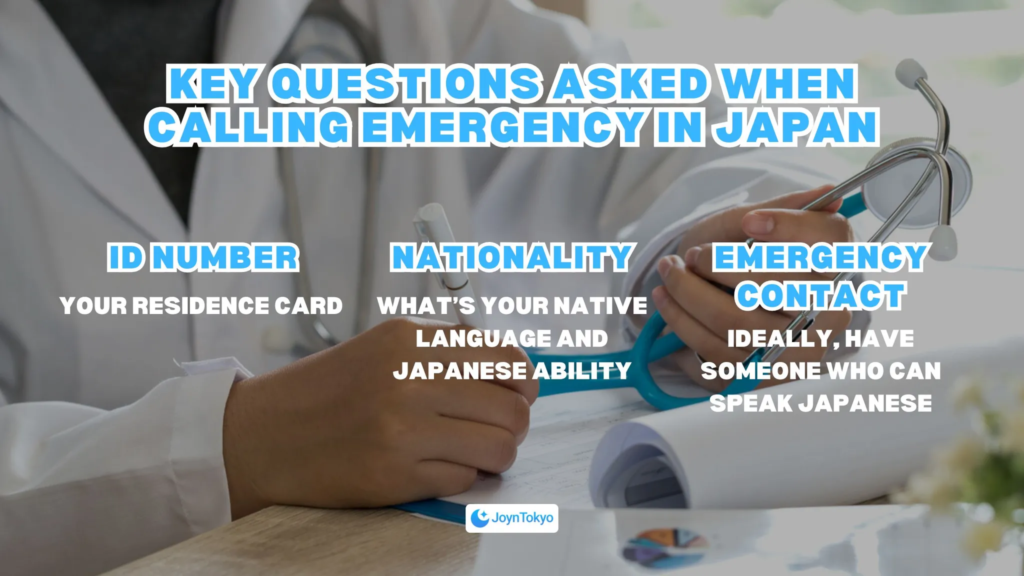

I’ll spare you the gorier details of how and why I came to be hospitalized, but I’ll take you through the process. The first thing that happened to me, upon calling an ambulance, was being helped inside, then being asked for my details. These included my ID, confirmation of my nationality and native language, and a question on my Japanese ability.

One other thing that is vital is to give an emergency contact. This should ideally be someone who can speak Japanese. When I tried to give the name and number of my father back home, the paramedics were understandably loathe to accept this: after all, in an emergency, things have to be done quickly, who can deal with timezones or translation? So, I gave them the name of a Japanese friend.

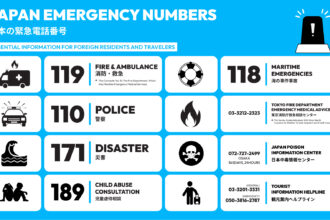

If you want to know more about contacting Japanese emergency services, please follow the link below:

Examination

Next comes the examination phase. Depending on your illness and symptoms, this can take a long or short time, but I went through an MRI, an endoscopy, and multiple blood tests. After this, as in many hospitals, came the waiting game.

This can vary depending on the severity of your condition. In my case, I waited for roughly an hour or so before being taken to a room to stay the night. After this, I was presented with a form mostly in Japanese, but partly in English, essentially asking if I wanted to stay in a private room, or a larger room with other patients, separated by curtain partitions. I opted to go with the larger shared room, as private rooms are not covered by Japanese health insurance, and can quickly become expensive.

After this, I was brought to my bed, which had a small cupboard for clothing and other articles (you are generally not permitted to wear your own clothes early in a stay, and are given a choice between a gown or jinbei-style pajamas). I also had to make a list of everything I came with, to ensure that everything would be accounted for when I left (though the hospital bears no responsibility for any lost materials).

Tests, Tests, and More Tests

After the initial shock you’ll feel after being brought in and told that, for the next week, this is your home, things start to settle into a familiar routine. Japanese hospitals like to keep people in for a week in order to keep an eye on you, not just throw medicine at you and see what sticks. When I was in hospital, I was told I’d have tests )bloodwork, X-rays, etc.) every day for the first few days, and should stick to bedrest.

Luckily, I had my phone, a charger, and some books, and my hospital provided WiFi for patients. These are essential as, without them, I would probably have gone mad. Being cooped up in a comfy bed all day is only an attractive proposition if you’re sleepy, but over a longer term, it’s frustrating.

You can expect regular check-ups and updates on your tests throughout your stay. For me, it was usually after a meal: after breakfast, the doctor consulted me about my tests that had been conducted, and those that will be during the day. At lunch, another update, and a final update after dinner.

This brings me to the next point: whether or not you get a doctor who can speak English is largely up to luck. I was lucky enough that one of my doctors spoke English, but on days he wasn’t there, I had to make do with the Japanese language skills I had. In Tokyo or other major cities, the likelihood of having at least one doctor who can speak English is greatly elevated. In more rural areas, it’s possible you may struggle to find such a speaker. However, many places will offer interpretation facilities.

Living in a Hospital

One of the benefits of being in a Japanese hospital is the food. I’ve been in a British hospital over around a week with a broken knee, and while the doctors and nurses were excellent, the meals were lacking a certain je ne sais quoi. This was not my experience in a Japanese hospital.

The food given is freshly made, and consists of a typical Japanese diet: rice, soup, vegetables, and a portion of fish (occasionally meat). Every meal was of excellent quality, and in other circumstances, I might feel that I was in a hotel (but for the beeping equipment).

Similarly, after the first few days, when I was allowed a little more autonomy, there was a conbini at the base of the hotel I could visit, to get money and small items. It was interesting to see a different kind of conbini: things like socks and underwear were on display in a way they aren’t in regular stores, and things like soda were relegated to a small amount, while alcohol, normally taking up a quarter of conbini refrigerators, was understandably absent.

On my ward, we also had some vending machines for things like tea and coffee, and many of us would get up and about to do a few laps of the floor, for some exercise, and to make friends. After all, we’re all in here together, right?

Another thing that was nice was the shower room. In truth, it had a large bath, but I suppose for hygiene reasons it was impossible to keep it full for everyone. I was always last in the rotation, which meant I got to shower last, but one benefit was that this meant I was able to go over the allotted 20 minutes per person, since no one was coming after me. The showers were well maintained, and had ample soap and shampoo.

Discharge

When you leave the hospital, you’ll almost always get an appointment for a check-up, to make sure that your treatment is going well, and that you’re still healthy. You’ll also get a bill for the time you’ve stayed there. You can expect 70% to be paid for by your health insurance, but the remaining 30% is going to be paid by yourself, by card or cash. In my experience, you will also get a card from the hospital, so that any follow-ups can be completed more quickly.

Final Thoughts

Nobody likes going to the hospital. It’s a scary and difficult time. But Japanese hospitals are clean, efficient, and provide excellent service. As a Brit, I did resent having to pay for healthcare a little, but it was worth every penny. I hope that you will never have to have a stay in hospital, but if you do, know that you are in good hands.