Going to the Doctor

Well, it was bound to happen sooner or later. Whether you’ve got a cough you just can’t seem to shake, or you’ve suffered an injury, you’ll almost certainly have to go to the doctor at one point or another during your time in Japan. And while it can be a little scary to go to the doctor, even if just for a routine check-up, it’s honestly not so bad. Let me take you through my experiences visiting the doctor’s office in Japan.

Know Who You Want to See

This might sound strange for some people, but in Japan, there is no real equivalent to a general practitioner, though many small clinics will have the designation “Internal Medicine” (内科) who can often diagnose minor issues. However, it’s better if you know where to go: a clinic across the road from me has been helpful with things like minor pains or sickness, but she was unable to help diagnose problems with my eyes or ears.

Knowing who you need to go to can also make things faster. Rather than needing to be referred from one doctor to another, if you know your problem, you can go right to the expert. After I twisted my ankle a few years ago, I looked up a nearby podiatrist, who was able to give me the help I needed right away.

Finding an English Speaking Doctor

Medical language is difficult even at the best of times, so trying to understand the differences between a perineum and a patella in Japanese can be a trial for anyone who isn’t a native speaker. If you’re in a major city, like Tokyo, you may get lucky: a clinic across the road from me has a doctor who speaks English because she studied in the US, and as it’s her clinic, she’s there every day.

It is the case however, that some places will only have English speakers on particular days. The podiatrist I mentioned earlier is excellent and helpful, but he only sees patients on Wednesdays. When I had to go in for a follow-up on a Thursday, I had to rely on a phone translator.

In smaller towns or villages, you may have to do the same, or prepare some phrases in Japanese first, as you may be unlikely to find an English speaking doctor. When I used to live in the relatively small city of Nishio, I was super lucky to have met an English speaking doctor, so even a nasty bout of stomach flu was easily managed. But on a trip to Hiroshima, I had to make do with what little Japanese I could get by on to diagnose an ear infection. Luckily, the doctor was sympathetic, and even wrote a note in Japanese to givr to another doctor if I needed my prescription refilled.

Opening Hours

Medicine in Japan, like in many other countries, is a business. While your care is 70% paid for by insurance, the clinics are not necessarily going to be open at all times. During Obon, I went to a local ear, nose and throat clinic to check on an ear infection… only to discover the doctor would be gone for the next week. Luckily, there was a larger clinic I knew open in central Tokyo, but they were running on a skeleton staff, and the English speakers had left to see their families in their hometowns.

In smaller town, again, you may have to rely on one or two clinics, so if you know you’re prone to certain illnesses as certain times when clinics may be closed (for example, over Golden Week), you might want to ask them for some medicine in advance to help you weather the time they are away.

Hospitals are typically a different matter, as you can imagine, but like anywhere else, there will be fewer staff at night, so if you are admitted in the evening or later, you might end up waiting a while. I remember being sat on a bed for nearly two hours waiting for the results of a simple test, once. Luckily, I had a book with me, so if you can, try to do the same.

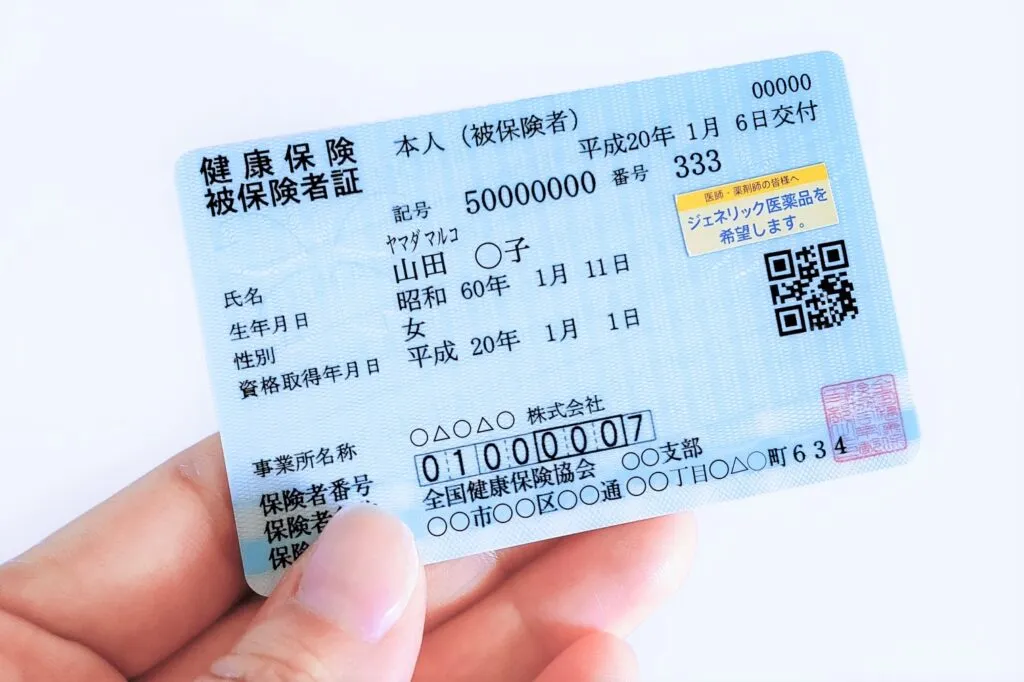

Insurance Card and ID

One thing you’ll always be asked when you go to the doctor is for your ID and insurance card, so that you can be entered into the system. Or at least, that was the case:

National Health Insurance cards are no longer being distributed, and your health insurance will be instead tied to your My Number card (Employer Health Insurance cards are unaffected. If you have an NHI card, you’re still okay to use it — until the grace period for transfer ends. Depending on where you live, this can be as late as December 2025, though some wards, cities, and prefectures have earlier cut-offs, so check your local government website for confirmation.

Because this is so important, I carry my health insurance card with me all the time (until I switch, then I will carry my My Number card). You never know if you’re going to get hit by a bike and need to go to hospital (this happened to me) or just need to go for a work mandated check-up (this also happened to me).

Paying and Reimbursements

One thing that may be familiar to some (though not to me — where I’m from, all healthcare is free) is the idea of payment and reimbursements. Whenever you finish your appointment, you’ll be asked to pay a bill. For many this will be normal, but as a UK citizen, it still irks me that I have to pay a doctor when I already pay taxes. That said, most minor things are small, around ¥1,000 or so. Even a broken bone cost me a mere ¥7,000, so those from countries with more expensive systems may find it amazing.

After I tripped out of nowhere a few times, I went to the above-mentioned podiatrist, who said that because I had flat feet, I should get orthotic shoe soles.

This is covered by insurance, but first I had to pay the full price up front. After this, I had to take the official receipt (or you can ask for a verified copy, if you lose it) to City Hall’s health insurance desk, fill out a form, and wait for a few months to be reimbursed. Usually, your doctor will ask for a 100% reimbursement, but the amount that you get back is largely at the discretion of the local government (though you’re likely to get most of your money back: I got ¥55,000 back from ¥60,000 for my special footwear).

It may be frustrating to have to wait — I know it was for me — but in some ways it’s like wearing an old coat and finding money inside: one day a few months later, you find more money in your account. But be aware that you need to apply within two years of your prescription, otherwise, you’re too late.

Repeat visits

The last thing is that, when you find a doctor (or dentist) it’s a good idea to stick with them, if you can. Whenever I’ve had problems, my regular doctor not only has all my records, but the doctor and staff remember me and the issues I’ve had, so they are able to give strong advice in context.

You might also be asked for follow-up appointments, and you should definitely go. I once forgot to go to a follow-up with my doctor across the road, and when I went back over a year later with a fresh complaint, she was pretty miffed at me (though still gave professional service and advice, of course). Like all things in Japan, maintaining relationships is important.

Final Diagnosis

Going to the doctor in Japan is, the first time, perhaps a little nerve-wracking, but it’s on the whole an easy and simple procedure, with just a few bureaucratic steps (common to Japan) and perhaps a couple of things you may be unfamiliar with.