Like many countries, Japan has a long history with everyone’s favorite intoxicating beverage. There are no religious edicts against alcohol in Shintoism, and sake — commonly thought of as Japanese rice wine — is used in certain holy rituals, much as wine is in Christianity.

But in today’s modern society, there are far more options than just fermented rice. So what alcoholic drinks are popular in Japan? What purpose does alcohol serve for Japanese people? And does Japan experience similar problems with alcohol that other countries do? Pull up a stool.

Popular Types of Japanese Alcohol

Japan is a consumerist paradise in many regards: if you can imagine it, chances are you can buy it. Nowhere is this more true than with alcohol. Liquor stores dot the nation, offering interesting drinks and knowledgeable staff who can give expert recommendations. But you can also find your tipple of choice in almost any convenience store in Japan: I’ve only ever seen one FamilyMart that doesn’t serve alcohol, because it is in a government building.

So what are the most popular drinks? Let’s run through the menu.

Japanese Beer

Introduced to Japan during the Meiji Restoration in the 19th Century, drinking beer was seen as trendy, as the country rapidly modernized and adopted foreign tastes. With the introduction of the refrigerator, which allowed people to keep beer cool in their own homes, the popularity only grew, and today it is Japan’s most popular alcoholic drink.

Beer can be bought from almost any convenience store and supermarket, with lager-style beers being the most popular. Among these, Asahi Super Dry is a prominent fixture as the most popular, while Kirin and Sapporo also have a huge number of fans. For a little more money, Yebisu and Premium Malts are sold as premium options, and are often the beer of choice for bars that serve it on tap.

While this might sound like it makes things difficult for real ale fans, Japan has been developing a craft beer scene, and some more niche beers, like Yona Yona, are available in convenience stores, while supermarkets and dedicated liquor stores will often have a wider selection. Additionally, larger cities like Tokyo have specialist craft beer pubs and bars, so there is plenty for you to sample.

Japanese Beer Culture and Seasonal Varieties

If you’re a beer drinker, then Japan is a terrific place to be. With mainstay lagers (Yebisu is my favorite, but your tastes may vary: try and see which is best for you!), craft beers growing in popularity, and seasonal varieties available even in convenience stores, there is always something for you to try.

Beer-like drinks (happoshu)

For those on a budget, though, beer can sometimes be a little pricey. Luckily, Japanese brewers have come up with a somewhat ingenious solution: happoshu (発泡酒). This is a “sparkling alcoholic drink,” and is used primarily to craft “beer-like” drinks. The reason they are so popular is that, by using less than 25% malts in their beverages, these can avoid the higher taxes placed on “real” beer, and those savings can be passed on to the consumer, though these are set to be normalized in 2026.

Most drinkers will tell you that, compared to a true beer, the taste is sharper, and less textured. The trade-off, in addition to lower prices, is that they can often have less purines, which can cause gout, and lower carbohydrates.

Popular brands include Nodogoshi, 7-Eleven’s The Brew, and Kinmugi. Some people consider these drinks to be a little bit like gut-rot, but they aren’t as bad as some believe — and if you’re counting your yen at the end of the month, then, hey, any port in a storm.

They’re sometimes sold in six-packs with a pickled fish, or something similar, and I recommend pairing them with something with a strong taste.

Japanese Sake (Nihonshu)

This is the drink that many associate with Japan, and for good reason. The equivalent of wine in the west, sake (酒) literally means “alcohol,” so many will call it “Nihonshu” (日本酒) to differentiate it from other types of booze. As mentioned, this typically 13%-15% strength rice “wine” has played a significant role in Japanese society for millennia.

Sake is used during wedding ceremonies, where the groom and bride will share the same cup, cementing their relationship, and is buried under sumo rings before every tournament as part of religious consecration. Even in Shinto shrines, where alcohol is typically banned as a sign of respect, omiki (御神酒) is sold, as this sake is sacred (literally translated as “alcohol of the Gods”) and used in purification rituals.

There are many kinds of sake, but the ones that are most commonly sold in convenience stores and supermarkets are Junmai (純米), which is sake made with the four basic ingredients of rice, water, yeast, and koji, a form of mold used to promote fermentation; Ginjo (吟醸), which uses a special kind of fermentation additives to create a more fruity flavor; Honjozo (本醸造) which uses brewers alcohol during fermentation to even out the taste; and Daiginjo/Daijunmai (大吟醸/第純米), a superior form of Junmai and Ginjo, using rice which has been deeply polished.

How Japanese Sake is Served (Hot vs Cold)

While sake is generally thought of as a drink to be consumed hot in the west, many higher-grade sake is perfectly enjoyed chilled (and may indeed be more delicious this way). Many supermarkets will have signs showing whether a sake should be enjoyed on the rocks, chilled, at room temperature, or heated. If in doubt, ask an employee, and they can help you.

Personal Experience with Drinking Sake in Japan

As for myself, hot sake in the winter is an absolute joy. Coming in from the cold and having a drink that not only is hot, but makes you feel warm (even if the affect of alcohol, which contracts you blood vessels, is to actually make you a little cooler) can making the biting winters of Tokyo that much more bearable.

But for the summer, a nice, cold glass is incredible. While typically small sake cups called ochoko have been used, often restaurants and bars in summer will serve chilled sake in glasses. This not only is cooling inside, but helps you forget, for a moment, the extreme heat of this often humid nation.

Shochu

Commonly referred to as “Japanese vodka,” shochu (焼酎) means “burned liquor,” but this is actually a reference to the heating used during the distillation process, not the feeling you get in your chest after a sip. Typically a minimum of 25% alcohol volume, it can be made from various ingredients, including rice, sweet potatoes, and barley, though even vegetables such as carrots have been known to be used in shochu distillation.

Because it is very strong, many people prefer to drink it split with water (known as “mizuwari”/水割り) than straight, but it can also be enjoyed on the rocks. It is the drink of choice for salarymen looking for a quick fix to unwind, and also in the southern island of Kyushu, where most of Japan’s shochu comes from.

Okinawa, even further south, also has awamori, a similar drink that is a little smoother going down, and is made with long-grain rice, rather than the typical Japanese short-grain rice.

I once forgot to put the stopper on a bottle of awamori, and by the time the morning arrived, a lot of it had evaporated.

How to Drink Shochu: Straight, Mizuwari or On the Rocks

It’s not my drink of choice: I don’t care for the flavor when drunk straight, nor am I especially keen on it on the rocks: it’s a little rich for my blood. But with water, if can be nice, and for those who enjoy spirits, it makes an interesting change from vodka, gin, or whisky.

Chuhai

A derivative of shochu, chuhai (酎ハイ/チューハイ) are drinks other than water mixed with shochu, to both enhance the flavor and take the edge off of the taste of the strong drink. These are popular in bars and izakaya, and can be bought in cans from convenience stores and supermarkets. That being said, often the canned versions, to keep prices down, will use cheap vodka from abroad.

The canned versions are often a hit with newcomers to Japan: they taste like fruit juice, and can give you a buzz pretty quickly. They are such a hit that convenience stores and supermarkets will often create their own brands. One of the larger brands that permeates all of Japan is Strong Zero, which sell 9% alcohol drinks on the cheap. Sometimes referred to as “salaryman crack,” these are known for getting people wasted, fast. Occasionally, even 12% special editions are sold.

Caution with Chuhai and High Alcoholic Drinks in Japan

The ease of drinking these, coupled with the higher than normal amounts of alcohol, mean that chuhai should be enjoyed with a degree of caution. If you are going to have one of the stronger drinks (from 7% or more) then I highly recommend eating to line your stomach both before and after.

Japanese Whisky

Famous throughout the world, in just under a century Japan has perfected this favorite of Europeans and Americans, with Japanese whiskies regularly winning awards as the finest in the world.

The story of Japanese whisky is fascinating. It began when Shinjiro Torii, an executive at the company that would one day become Suntory, a Japanese beverage mega-corporation, and chemistry graduate Masataka Taketsuru, who apprenticed at a whisky distillery during his studies in Glasgow, Scotland.

Torii eventually decided that the rough, peaty flavors of traditional Scotch whisky was too harsh for the Japanese palate, and so developed a smoother, more delicate style. Taketsuru, who favored the old ways that he had learned, set up his own company in Yoichi, Hokkaido, which he felt had the closest similarities to Scotland in terms of climate. His company is today known as Nikka, and the split between the two men and their whisky philosophy continues to shape whisky in Japan to this day.

Whisky is today widely available, both Japanese and imported American and Scottish whiskies. However, while you can buy whisky at convenience stores, you will likely only be able to get cheap Japanese varieties, or common American brands, such as Jack Daniels. Going to a supermarket or a specialist liquor store will open up worlds of choice and understanding of Japanese whiskies. You can even find rare gems hidden away in the dusty corner of a small family booze joint, if you’re lucky.

Japanese Whiskey Bars and Global Recognition

Whisky is not my tipple of choice. But if you are a fan, there are many whisky bars (I have had the fortune to take friends to a small place near me called 3rd Shots in Ota-ku) as well as the magnificent Whisky Library, which has hundreds of whiskies from all around the world for you to sample.

Japanese Wine

One thing that you might have noticed as conspicuously absent from the list is wine. While Japan does produce wine, it is not famous for it, with the climate and terroir presenting some difficulties. That being said, Hokkaido’s cooler climates, and Yamanshi prefecture’s warm valleys mean that Japan is capable of developing wines with distinctive characteristics, and some critics are beginning to recognize Japan for its viticultural potential.

That said, you can find foreign wines in many places. Following the adoption of the Japan-EU Economic Partnership Agreement in 2019, wines from the EU are less expensive than they once were. Additionally, Chilean wines enjoy reduced tariffs from Japan, making them popular in supermarkets, convenience stores, and bars.

Umeshu – Plum Wine

One other treat that screams “Japan” is umeshu (梅酒) or plum wine. The name is deceptive, however: this tasty cup is made by steeping unripe plums into shochu, with a heaping of sugar. The result is a sweet, somewhat thick plum-tasting liqueur.

Regularly enjoyed in summer, it is easy enough to create that many families make their own umeshu at home, though you can buy it easily from convenience stores and supermarkets, with choya being the most famous brand. It is not at all unusual to see bottles with the plums still inside them, and is indeed considered a mark of authenticity.

Drinking Culture in Japanese Society Today

While Nihonshu is used in ceremonies even to this day, it is, like many places, used as a social lubricant and a way to unwind during difficult times. There are, however, some unique aspects to Japanese drinking culture. Let’s go through a couple.

Nomikai

“Nomikai” (飲み会) means, “drinking meeting,” and it’s more or less what it sounds like. As you may know, many Japanese workplaces are known for being stressful, and require long hours. So often, companies will organize evenings for the employees to let loose, and have a few drinks.

This is not just to blow off steam, but to allow for greater camaraderie between employees. Maybe your manager is demanding, or your subordinate isn’t pulling their weight, but it’s hard to be mad when the great equalizer of intoxication brings you together. These can often be paired with dinner, or karaoke.

Relaxing after work

Along a similar line, and something that will be familiar to most, is the impromptu drinks with a colleague after work, or even heading by yourself to your local izakaya to hang out with other regulars. This is a pretty common experience, and is often concluded with “shime ramen”: getting ramen noodles, filled with carbs, veggies, protein, and broth, to keep you from being hungover the next morning.

Getting to Know People

Again, this will be familiar to most, but if you’re going on a date, or have made a new friend, it’s common to go for a drink to get to know one another, and get a little looser as your beer, chuhai, or Nihonshu set you at ease.

But this reliance on alcohol for relaxation does come with some drawbacks.

Problems of Alcohol Culture in Japan

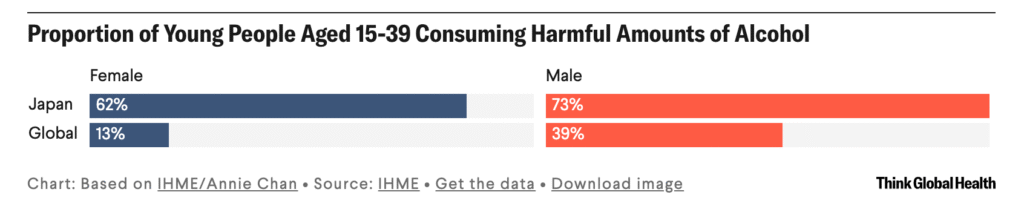

Because Japanese people have a reputation for enjoying a glass or two, and there is no social stigma against drinking (within limits), there is also a slow and insidious culture of “quiet alcoholism” that can develop. According to Think Global Health, 73% of men in Japan aged 18-39 drink excessively, compared to 39% globally, with 62% of women in the same age bracket drinking dangerous amounts, compared to a global average of 13%.

Some doctors have been highlighting this as a growing problem, especially as, while the relaxing drinking activities above don’t have to be bad, many Japanese people are using alcohol as a cheap substitute for therapy.

Alcohol Consumption Amongst Young People in Japan

However, especially among young people, alcohol consumption rates have begun to fall. The government has attempted to encourage more drinking, in order to make up for lost tax revenue, but many are remaining either teetotal, or drinking less regularly, or drinking smaller amounts.

Alcohol companies have reacted quickly to this trend, and today there are many non-alcoholic drinks that can let you feel like you’re enjoying a beer with your buddies, without touching a drop of ethanol. Asahi produces a number of non-alcoholic beers, many of which can be found in convenience stores and supermarkets.

Non Alcoholic Options in Japan

You can even find non-alcoholic chuhai and other cocktails in cans, and some supermarkets also sell non-alcoholic wine. Low-Non-Bar also opened in 2020, Japan’s first non-alcoholic bar, with plenty of mocktails and non-alcoholic options.

There are also drinks such as “Beery” by Asahi, which do contain alcohol, but a mere 0.5%, so you are in no realistic danger of getting drunk.

Drinking alcohol in Japan is much like it is anywhere at a fundamental level: it should be enjoyed in moderation, and as part of a healthy lifestyle. But the variety of options, the history behind the drinks here, and the options for where and how to enjoy it mean that this is a terrific place for anyone looking for a quick drink, or to explore the depths of thousands of years of brewing and distillation culture.