Japan’s Human‑Rights Framework

Japan’s post‑war democracy is built on a constitution that loudly declares the nation’s dedication to equality and freedom, and the government regularly advertises a “rules‑based international order” in diplomatic arenas such as the UN. Nevertheless, the distance between principle and practice can surprise newcomers, making it worth mapping the formal landscape before you step into daily life here.

Constitutional Protections

Articles 11–14 of the 1947 Constitution enshrine individual dignity and explicitly ban discrimination on the grounds of “race, creed, sex or social status”, while also guaranteeing freedoms of speech, religion, residence and assembly. Although these clauses are sweeping, enforcement depends on ordinary legislation, court decisions and, crucially, the willingness of individuals to litigate — so outcomes can vary by locality and by the determination of the people involved.

International Commitments

Japan has ratified all major UN human‑rights treaties, including the ICCPR, the ICESCR and the Refugee Convention, and subjects itself to periodic UN reviews. Successive administrations highlight this record to bolster the country’s soft power, yet international differences on asylum, hate speech, and marriage equality continue to pile up, underscoring unfinished work at home.

Gaps of Oversight

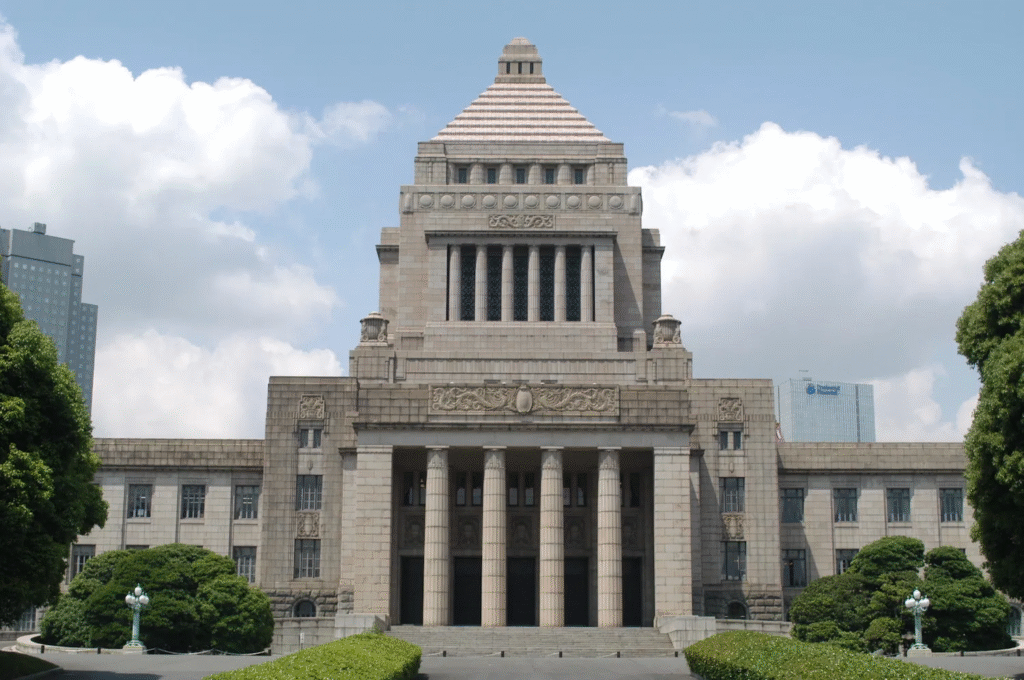

Despite repeated Diet debates, an independent national human‑rights commission has never been established. As a result, investigations often fall to over‑stretched local ombudsman offices or to the civil courts, where high legal fees and lengthy timelines can deter victims from seeking redress.

Everyday Rights You Will Encounter

Japan is famously safe, orderly and convenient, yet none of those qualities guarantee that every institution — or every landlord and employer — treats non‑Japanese residents fairly. Understanding your rights can nudge any potential encounters in a better direction, and help you recognize where and when you may push back.

Free Speech and Peaceful Assembly

Protest marches around the National Diet building remain a staple of Tokyo civic life, and permits for large gatherings are usually processed without incident. Online expression is broadly protected, but civil defamation suits are common, and a draft “false information” bill that is now working its way through parliament has triggered lively debate in newsrooms and civil‑society circles.

Work, Visas and Labour Standards

The Labour Standards Act applies equally to foreign and Japanese workers, covering minimum wage, overtime pay and workplace safety. In practice, many foreign residents hesitate to lodge wage or harassment complaints because their ability to stay in the country is believed to hinge on employer sponsorship, which is a weakness that labor unions are trying to address through collective agreements, multilingual hotlines and public‑awareness campaigns. When it comes to sexual identities, under the 2023 Understanding LGBT Act, employers must now “take measures” to prevent harassment based on sexual orientation or gender identity, but the statute stops short of creating a private right to sue or imposing fines.

Privacy, Digital Rights and AI

Japan’s Personal Information Protection Act, revised in 2022, borrows heavily from Europe’s GDPR and grants individuals the right to demand explanations for data collection. Meanwhile, a new AI Promotion Bill, approved in early 2025, introduces non‑binding guidelines for facial recognition and algorithmic decision‑making, signalling a preference for light regulation over rigid bans and ushering in a fresh round of digital‑rights debates.

Current Challenges and Reform Trends

Despite constitutional safeguards, several pressing human rights issues in Japan continue to draw domestic and international criticism.

Anti‑Discrimination and Hate Speech

A 2016 Hate Speech Act condemns racist rallies, but sets no criminal penalties, leaving real muscle to a patchwork of municipal ordinances in cities such as Tokyo, Osaka and Kobe. Police stop‑and‑search of foreign residents — especially those of African or South‑Asian descent — continues to be reported, despite official training programs aimed at curbing such profiling.

Gender and Sexual‑Minority Equality

High courts in Sapporo, Tokyo, Fukuoka, Nagoya, and most recently Osaka (April 2025) have declared Japan’s failure to recognize same‑sex marriage unconstitutional or nearly so. Momentum is clearly building, yet the Diet has so far offered only symbolic recognition and limited partnership registries, leaving couples without inheritance rights, joint tax filings, and incapable of gaining spousal visas. The Supreme Court’s 2023 ruling that forced sterilization for transgender people is illegal marked another milestone, but surgery requirements and outdated family registries still complicate the path to legal gender change.

Immigration Detention and Asylum

In 2024 Japan revised its Immigration Control Act, introducing community‑based “supervisory measures” for some applicants while also permitting deportation after two failed asylum bids. Approval rates, stubbornly below two percent, reflect a culture of suspicion toward refugees, and rights groups continue to document cases of prolonged detention, constrained legal access and inadequate medical care.

Criminal Justice and the Death Penalty

In Japan, suspects may be interrogated without a lawyer present, and be held for up to 23 days before prosecutors file charges — a period critics label “hostage justice.” Once in court, a heavy reliance on confessions means that conviction rates have been pushed above 99%. The death penalty, still carried out by hanging, remains on the statute books, and families are notified only after the execution has taken place.

How to Act if Your Rights Are Violated

Knowing where to turn can make a critical difference when problems arise.

Government Helplines

Ministry of Justice Human Rights Hotline (0570‑090‑911): Provides multilingual advice and can mediate discrimination complaints.

Local Labour Standards Offices: These organizations investigate wage theft, unsafe conditions and unfair dismissal, as well as offer interpretation support.

NGO and Legal Aid

Human Rights Now, Amnesty International Japan, and the Japan Federation of Bar Associations run pro‑bono clinics, publish know‑your‑rights handbooks and escort independent observers into immigration detention centers.

Practical Steps

- Document Everything: Write down names, dates, badge numbers of police officers, and direct quotations as soon as possible, and secure photographs or recordings when legal.

- Create a Paper Trail: File complaints in writing and request a stamped copy. This simple step often prompts quicker action from the necessary authorities.

- Escalate Data Issues Quickly: For personal‑data misuse, submit an online petition to the Personal Information Protection Commission, which can issue corrective orders.

- Know the Emergency Numbers: Dial 110 (police) or 119 (ambulance) without hesitation: operators generally connect you to English assistance if you speak slowly, and clearly identify your nationality.

Outlook for 2025 and Beyond

Japan blends low crime, efficient public services and a vibrant civil society, yet that has noticeable gaps in anti‑discrimination coverage, and an immigration system still geared more toward control than protection. Court victories on marriage equality and transgender rights suggest gradual but real change, and new digital‑rights debates around AI hint at future regulatory reforms. For foreign residents, staying informed, asserting your rights early and building connections with advocacy networks remain the most effective strategies for a secure, confident and fulfilling life in Japan.