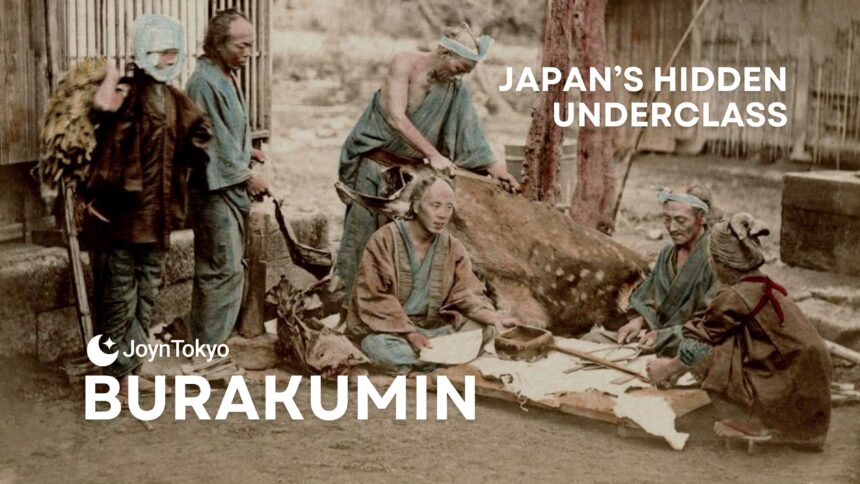

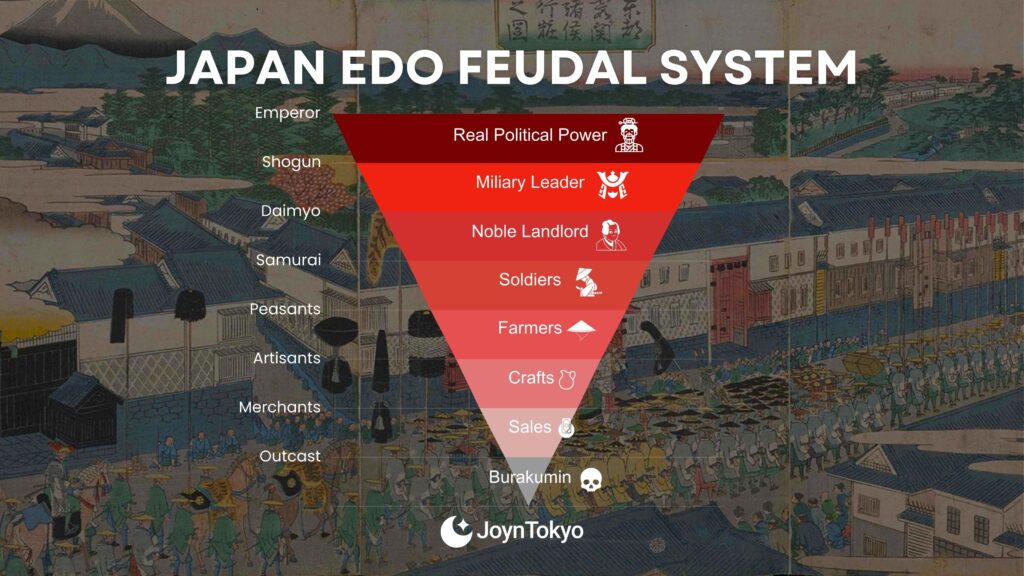

Japan has a long and rich history, with a lot to be proud of. But that doesn’t mean that everything that has been done here is worth celebrating. Like many countries that had feudalist systems, Japan’s feudal era resulted in an entrenched hierarchy that was difficult to change, or to elevate one’s status from within. Nowhere is this clearer than with Burakumin, a class of people “outside” of the feudal system, whose historical discrimination has echoes even to this day. Let’s take a look.

Who Are the Burakumin?

Burakumin are an interesting case when it comes to discrimination: they are almost all entirely ethnically Japanese, and their bloodlines stretch back hundreds, if not thousands of years. But it is just that history that has been leveraged against them. They have played a major and crucial part of Japanese life and society since at least the Heian period, but sadly, have been discriminated against since that time, as well.

Etymology and Meaning of Burakumin

Burakumin (部落民) initially seems somewhat innocent enough: “buraku” translates roughly to hamlet, while “min” simply means “people,” in a collective sense (for example, shimin (市民) means “city people,” or as they would normally be called, “citizens”).

However, they were not given the same consideration as ordinary citizens, being discriminated against generally since the beginning of the second millennium, and having their status as practically “untouchable” codified during the Edo period (1603–1868).

Originally a part of the sub-feudal strata of senmin (泤民), or “lower caste,” which consisted of hinin (避妊), or “subhumans”, and eta (穢多) or, “greatly filthy.” Because such people were not permitted to live with others, they typically resided in small enclaves and villages, hence becoming “hamlet people”: Burakumin.

Role in Feudal Japanese Society

In feudal Japan, it was understood that meat, though not eaten in large quantities, was healthy and delicious, and that leather goods were durable and useful, and criminals that were sentenced to death had to be executed. All of these tasks would have been performed by Burakumin. They carried out essential, but poorly paid functions that were necessary for feudal Japan to function.

But this begs the question: if they were so needed in Japanese society, and without their labor, the feudal system could have risked collapse, why were they discriminated against?

History of Burakumin Discrimination

The history of discrimination against Burakumin is long, and sad. Despite being necessary to the functioning of Japan, they were cast out of towns and cities, and had basic human rights curtailed. But why?

Why Were Burakumin Discriminated Against?

Shinto is a religion that concerns itself deeply with purity, where blood, death, and filth are considered capable of making someone impure. Japan’s second religion, Buddhism abhors the eating of flesh, especially if the animal has been killed specifically to provide it, and has similar concerns about leather goods and the killing of people.

Read More

These facets of the two faiths, combined with a society which was accustomed to eating meat, using leather and tanned goods, and executing criminals, meant that those who actually did the things that people wanted done were outcast. It was very much a case of the peasants, samurai, and noble classes wanting to have their cake and eat it: they wanted the services Burakumin provided, but were simultaneously angry that they existed.

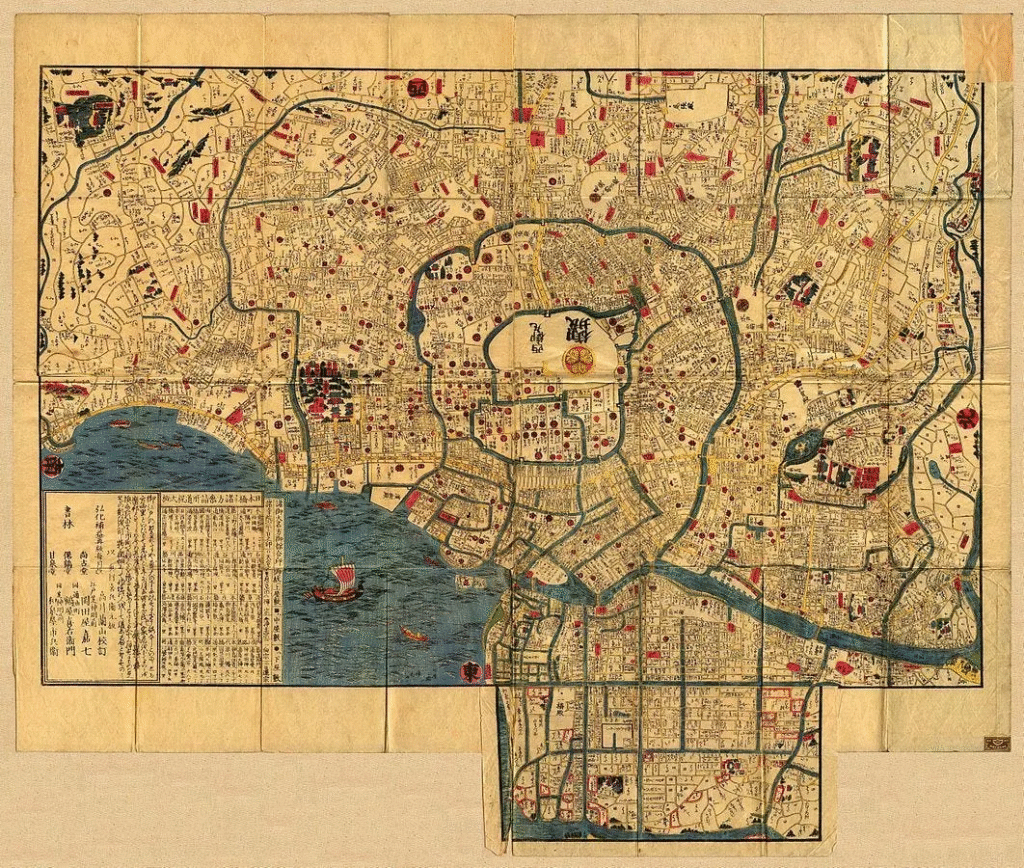

As such, Burakumin were denied access to housing in cities — or, in the case of large cities, such as Edo, which would later become Tokyo, relegated to impoverished neighborhoods, next to sex workers and other outcasts, many of whom enjoyed a higher public perception than Burakumin.

As such, the Burakumin were relegated to performing roles that were considered religiously impure, in the service of the religion that they had to follow, but which rejected them. Their pay was low, and they could rarely escape the status of Burakumin without paying large fees. Worse, being an outcast was hereditary: if you were Burakumin, so would your children be, even if they did not, for example, slaughter livestock.

Legal Status of Burakumin in Pre-Modern Japan

Legally, Burakumin had few rights. They were even forced to adopt certain hairstyles and clothing, were banned from entering homes or even temples without permission, and were scapegoated by the government for any ills that the country faced. Yet, this same military government needed jailers, torturers, and executioners for enemies of the state. All impure roles, all conducted by Burakumin, none recognized or well rewarded.

This made them economically reliant on the government for their roles: and in the event that none were forthcoming, they had to beg, or do difficult, demeaning work for peasants and merchants, who could pay them very little.

Did Legal Reforms End Burakumin Discrimination?

With the dawning of the Meiji Restoration, the caste system was abolished, meaning that Burakumin were no longer a de jure subclass. However, they also lost their exclusive right to carry out activities such as carry out executions or dispose of dead bodies. This meant that non-Burakumin, who had the money to undercut Burakumin business and who no longer had to worry about the stigma, could take over their traditional works, which actually left them even worse off than before.

Through it all, discrimination continued. Burakumin were denied employment or social gains not through law, but because their changed legal status did little to change the minds of the general Japanese population (unless they were looking for extremely cheap labor).

Additionally, at the time, it was easy for any family (typically the father) to request the family records of someone outside of the family. As such, if a Burakumin managed to escape poverty, become respectable, and want to marry, it would often be denied, because the family would not permit their son or daughter to marry a Burakumin.

Burakumin in Modern Japan

The defeat of Japan after the Second World War led to many societal changes. However, as we learned during the Meiji Restoration, changes in law don’t always result in changes in attitude or circumstance. So what are the problems faced by Burakumin today?

Problems Faced by Burakumin in the Modern Age

The most significant issue is that, given the massive economic disenfranchisement that Burakumin have suffered for centuries, it makes it very difficult to move out of the small places to which they were relegated, whether they be villages or neglected urban areas. It is even sometimes the case that train stations near areas with Burakumin populations will have defamatory graffiti “warning” passers-by.

Burakumin are still often made to work difficult jobs, such as those in construction, for low pay. Many Burakumin, for example, worked to rebuild Tokyo after the Second World War and prepare it for the 1964 Olympics: a set of games almost none of them would be able to see, despite building the stadiums.

Additionally, the poverty that marks out many Burakumin families mean that many are forced to turn to organized crime, with some estimating that the Yamaguchi-gumi, the largest organized gang in Japan, has a membership of around 70% Burakumin.

Advances That Have Been Made

Despite the long prejudices against Burakumin, there have been many strides made in the last century. The Buraku Liberation League (BLL), founded in 1955, has led numerous successful campaigns to promote Burakumin advancement and reduce stigma and discrimination.

For example, the BLL’s co-ordination with the Japanese government resulted in the 1965 Special Measures Law, which saw big investment into Burakumin communities until the law was allowed to lapse in 2002. The BLL, while rightfully proud of the work that was done under this law, is still critical of the government for not doing as much as it could for the Burakumin community.

Furthermore, in 1976, the BLL managed to convince the government to prevent free public access to family registries, which helped reduce discrimination by making it dramatically more difficult for employers or patriarchs to find out whether or not someone was from a Burakumin background. It also convinced local governments to close loopholes allowing private investigators to get access to the same records.

Burakumin Activists and Notable Burakumin

Burakumin, especially in the modern age, have been active in working to assert their basic human rights. They have often met with success and acclaim, both within Japan and from outside, where global human rights advocates have praised Burakumin activists and groups for their steadfast dedication to ending discrimination.

Jiichirō Matsumoto – Leader of the Buraku Liberation Movement

Born in 1887 in Fukuoka, Matsumoto was one of the first generation of Burakumin whose discrimination was not legal, but was still a fact of life. He founded a construction company that hired other Burakumin, and used the profits to help his project to end discrimination against his people.

He went on to become a founder of the National Levelers’ Association, or *Zenkoku Suiheisha (*全国水平社), which advocated for Burakumin liberation and equality, refusing to work within the confines of government-mediated groups.

A committed socialist, he opposed militarism and was elected to the Diet both before and after the Second World War, and remained a devoted servant to the people while also working for the BLL. He died in 1966, and 10,000 people attended his funeral. Today, he is known as “the father of Buraku liberation.”

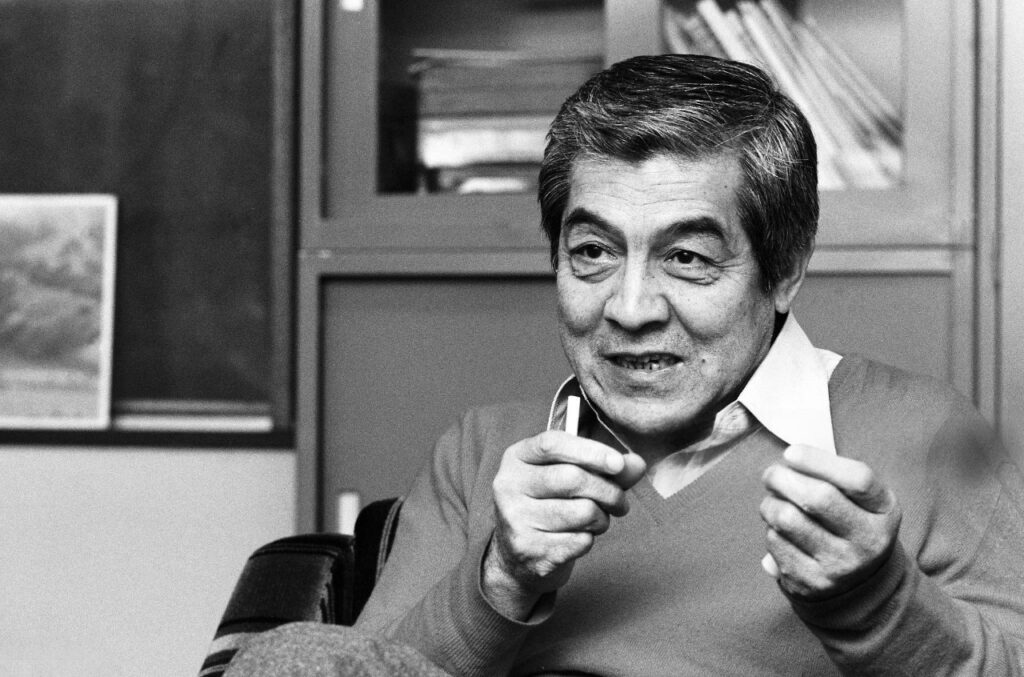

Hiromu Nonaka – Burakumin Politician

Born in Kyoto, 1925, Nonaka began working at a railroad after leaving school, but the discrimination he faced as Burakumin convinced him to leave, and instead become a politician in order to try and end such discrimination.

He soon rose through the ranks of local politics, eventually becoming the deputy governor of Kyoto, before being elected to the House of Representatives (taking a period in-between to be the chairman of the first facility in Japan for people with profound physical disabilities.

As a member of the Diet, and as a member of government, he was considered a cool head, and a voice of reason. His experience in local politics helped him strengthen his Liberal Democratic Party when it was in opposition. He was even considered to be a potential future Prime Minister, but was reluctant to go ahead. When Taro Aso, a future Prime Minister, brought up his Burakumin ancestry as a pejorative, Nonaka said he would “never forgive” Aso.

Before his death in 2018, he worked to strengthen relations between Japan and China, and was vehemently opposed to Japan revising Article 9 of the Constitution, which forsakes war.

Rentaro Mikuni – Actor and Burakumin Advocate

Born in Gunma, in 1923, Mikuni had a wild childhood: skipping school, running away to China, and trying to evade his military draft because he refused to kill or die. He eventually served as a medic, and after the war, returned to Japan to begin his career as an actor.

He soon became popular, but drew the ire of studios becuase he refused to stay exclusive to his contracts, and would take any role he found interesting. As such, a legend arose that a Kamakura studio placed a sign that said something the the effect of: “The Following Are Unwelcome: Dogs; Cats; Mikuni”.

He also “came out” as Burakumin in the 1970s, having become one of the most recognizable stars in Japan. Though this was downplayed by the press at the time, and even during obituaries at the time of his passing in 2013, many see it as a bold action to have taken. It also goes a long way towards explaining his distaste for authorities and rigid structures.

There are many darker aspects to the past of Japan, as there are for any country. The history of Burakumin is one of those. But Burakumin have been working to end discrimination against themselves — and often against others — for generations. While the struggle is not yet concluded, many huge strides have been made, and the BLL and other groups will not rest until dsicrimination is ended.