Omikuji are one of the most accessible traditions for anyone who wants to connect with Japanese culture. Whether you visit a shrine casually or during important moments in life, drawing an omikuji provides a small but meaningful window into Japan’s spiritual practices. This guide explains what omikuji are, how to read them, what to do with bad fortunes, and where to find English-friendly options.

Understanding the Cultural Meaning of Omikuji

Before exploring how omikuji work, it helps to understand why they remain important in Japanese society. Although many people today treat them as a fun activity, the origins are rooted in ancient divination rituals used to seek guidance from the divine. These rituals shaped the way communities interpreted good fortune, bad luck, and the flow of everyday life. Even now, that old sense of reverence lingers beneath the casual excitement of drawing a fortune slip.

What is an Omikuji?

Omikuji are fortune slips found at Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples across Japan. They offer predictions about various areas of life such as work, health, travel, and relationships. While simple in appearance, each slip reflects centuries of tradition and conveys thoughtful advice meant to guide visitors.

How to Draw and Interpret an Omikuji

The act of selecting an omikuji may seem simple, yet every part of the process reflects layers of tradition. People are drawn to it because it mixes luck, custom, and a quiet moment to look inward. The small pause before opening the slip often builds a sense of anticipation, and the result, good or bad, becomes a brief conversation between the visitor and the shrine’s spiritual atmosphere.

How to Draw

Most shrines ask for a small donation, typically between ¥100 and ¥300. Visitors then shake a wooden box, pull a numbered stick, or draw a slip directly from a container. This brief act symbolizes seeking insight from the divine, making the ritual both simple and spiritually engaging.

Understanding Fortune Levels

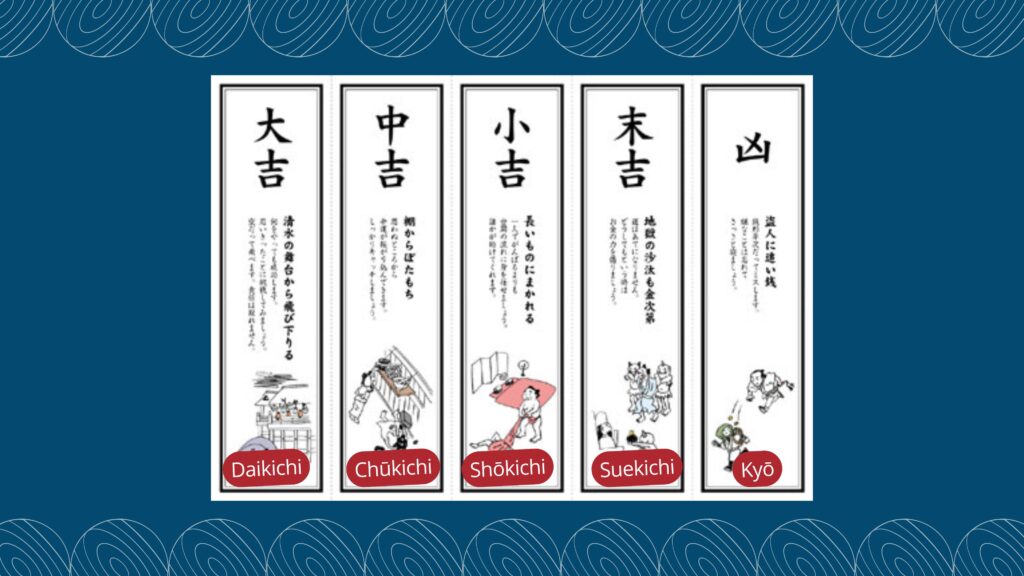

Omikuji follow a ranked system rather than a simple good-or-bad outcome. Common levels include Daikichi (great blessing), Kichi (good fortune), Chūkichi and Shōkichi (medium or small blessing), Suekichi (future blessing), and Kyō or Daikyō (bad fortune). Beneath the main label, detailed explanations provide advice about when to take action, when to wait, and what to avoid.

What to Do After Drawing Omikuji

Once you receive a fortune, you can either keep it or tie it on the shrine grounds. Both choices are acceptable, and each carries its own meaning.

Keeping or Tying

Good fortunes are often kept in wallets or bags as reminders of encouragement. If you receive a bad fortune, tradition suggests tying the slip to a designated rack or tree, symbolizing that the misfortune will stay behind rather than follow you home. Many find this practice comforting because it provides a physical way to release negative feelings.

Modern, Unique and English-Friendly Omikuji

As shrines welcome more international visitors, omikuji continue to evolve in creative and practical ways. These new formats allow foreign residents to enjoy the tradition with greater understanding. They also highlight Japan’s effort to make cultural experiences more inclusive.

Some shrines offer omikuji shaped like animals or charms, making them popular keepsakes. Others feature mizu omikuji, where the written message appears only when placed in water, adding a playful and magical touch. Major shrines in Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka often provide English versions, allowing foreigners to fully understand their fortunes without confusion.

Omikuji offer more than just a prediction, they create a small pause for reflection within daily life. They are especially meaningful during New Year’s visits or seasonal events, when many people seek guidance for the months ahead. Understanding how to draw and interpret them adds depth to the experience, revealing how this tradition has quietly shaped everyday spirituality in Japan. The simple act of opening a fortune slip becomes a reminder of how old customs continue to resonate in the present.